Table of Contents

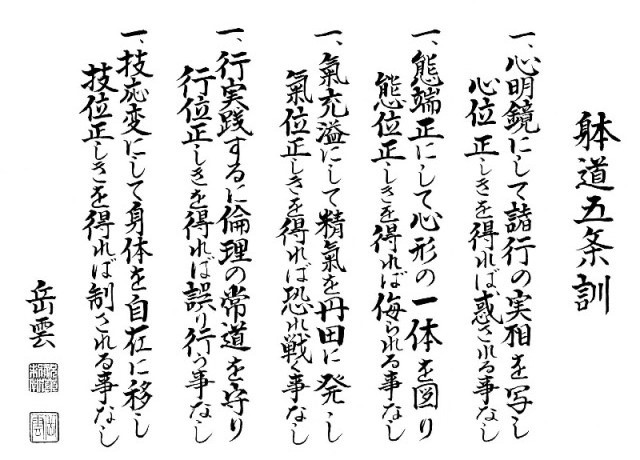

The gojokun (or five guiding principles) is the set of statements that forms the heart of Taido 's philosophy.

Since it is prescriptive rather than descriptive, the gojokun acts as a sort of mission statement for Taido. Though it gives us a few ideals to shoot for, it doesn’t offer much in the way of practical guidance.

Through the years, several several people have tried their hands and coming up with a suitable English version. I will discuss a few of them and present my own thoughts on what the gojokun says, what it means, and what we should do about it. With any luck, this article will get to the point of what can be a very frustrating mission statement.

What is Taido Gojokun?

What’s the point of the gojokun? That’s difficult to say. Though some dojo require students to chant gojokun in unison at the end of class, very few Japanese Taido students show any evidence of giving any thought to what they are saying. It was a rare thing that the five principles would be discussed while I was a young student in America - I memorized them at one point but was given no inducement to ponder their meanings.

Why Bother?

I think this begs the question of why we even have the gojokun. I have an answer.

Taido can be a very complicated martial art. We have three kamae, eight steps, several gymnastic movements, five body movement types, five control methods, kicks, punches, and other techniques... It can be a lot to think about. The gojokun has the potential to clarify things in that it offers us Five Simple Rules (5SRs) for practicing and applying Taido. The problem is extracting those precepts from the verbal fog.

Translating and Interpreting

The primary problem with the original 5jokun is typical of Japanese philosophy. Even in Japanese, the 5jokun is pretty vague, and in my opinion sacrifices applicability for the appearance of depth. This isn't necessarily a bad thing if you are talking about poetry, but I like my "guiding principles" to be clear and direct. What's the point of having Five Simple Rules if they don't mean anything?

Of course, they do mean something - they mean several things - but most students don't really know what that is, and aren't going to be able to figure it out without a lot of conjecture and uncertainty. Even in the original Japanese, students have to do a lot of interpretation to get anything out of the gojokun (I’ll look at why this is so a bit later).

Honestly, I don’t think the gojokun can be translated into English words that the western mind will readily "get" without taking a good deal of artistic license. Since English and Japanese operate on different operational principles, they convey meaning in different ways. Indeed, English speakers and Japanese speakers think in different ways - I’ve discovered that some thoughts are easier for me to think in Japanese. Since thought is inherently linguistic, it stands to reason that the grammatical structure of a language affects the thought patterns of the people who think in that language.

Part of the difficulty is that we can interpret the 5jokun in various ways, none of which would be present in a literal translation. There are translations biased to different applications of each principle, but this requires students to study several interpretations to understand what Taido is really all about. By doing so, we end up defeating the purpose of the 5SRs because we need to extrapolate four or five versions of each.

All this is just to say that any simple translation of the Japanese gojokun into English will probably leave a lot to be desired. There have been three of four attempts to my knowledge at such a translation, but none of them have meant very much to people who weren't already experts. Experts don’t need simple rules, but students do.

What it Says

The gojokun is structured around five sets of two statements. The first statement describes an ideal. The second statement is an “if/then” showing the benefit of achieving that ideal. For example, I could say this:

Brush your teeth after meals and before sleeping. If you keep your teeth clean, you won't have cavities and gingivitis.

This structure gives us a directive and a reason for each point. I’ll analyze these in more detail later. But before we can go much further, we need to look at a couple of the existing English translations.

The Official Version

Here’s the official English version of the Taido gojokun that most people have seen:

- Keep your mind as clear and calm as the polished surface of a mirror. This way you will see to the heart of things. Having the right state of mind will help you avoid confusion.

- Be composed. Body and mind should be as one. Bear yourself correctly and you need never fear insult.

- Invigorate your spirit from the source of energy deep in your abdomen. With the right spirit you will never fear combat.

- In every action, follow the correct precepts you have been taught. By doing so you cannot act wrongly.

- Be adaptable in your techniques and maintain freedom of physical movement. The right technique will prevent you from being dominated.

This is pretty literal. As a result, it doesn't feel like English when I read it. It has clumsy construction and odd-sounding fancy words in place of simpler words that are easy to understand (”bear yourself” instead of “act,” “invigorate your spirit” instead of “focus your energy,” etc.). It also sounds as if the author was trying a little too hard to sound philosophical by using passive-negative construction (”you need never fear insult” instead of “others will respect you,” etc.).

It’s not so much that it’s difficult to understand - it isn’t - but it reads like a fortune cookie. That’s great for haiku, but not for the 5SRs. What does it mean to invigorate one’s spirit from the source of energy deep in one’s abdomen? How can I tell if my spirit has enough vigor? What is this energy source, and how do I use it? Is that really all it takes to keep from fearing combat?

This vague language dances around the point without actually giving us any real guidance. But wait, it could be even worse...

An Older Version from America

This is what I learned as a child and wrote about for my shodan test. Rest assured, I didn't have a clue what this meant until I had given it a lot of thought.

- If the mind is tranquil and searches for the teachings of the true state of affairs, one will acquire the righteousness of never being perplexed.

- If the behavior is dignified - the mind and appearance - one will never be despised.

- If the feelings are concentrated, vigor comes from internal nerve centers. If one has right feelings, he will never be threatened.

- In every action follow the correct precepts you have been taught. By doing so, you cannot act wrongly.

- The techniques change appropriately from offense to defense. One who acquires correct adaptability to these techniques will never be restrained.

Wow. What a nightmare.

I want to “attain righteousness” as much as anyone else, but I’m not sure how that fits in with the things I practice in Taido. No wonder nobody in America seems to remember these, though I once found that it's a lot easier after a few cups of sake. This is a fine example of a totally unusable text.

So What is it really Saying?

That's a really good question.

Both of the above translation efforts use a lot of words and end up saying very little. The only way to get at what the gojokun is supposed to be teaching us is to take a more interpretive approach.

Interpreting the Gojokun

A few years ago, Lars Larm wrote a paper translating and interpreting the gojokun. It’s very good, and I would love to recommend you check it out, but it doesn't appear to be available any longer.

Lars made some good points regarding the difficulty of translating adequately and the necessity of interpreting the points for use by an English-speaking audience. He also gave ideas about how each point can actually be used, and this is very good.

However, all of this interpretation (and multiple versions of certain points) takes up a lot of space.

One important thing Lars did was to relate the gojokun to the five suki: mind, preparation, energy, decision, and technique. By looking at the gojokun in light of these openings, we can get a better perspective on how this philosophy relates to use in actual combat.

My Interpretation

The first principle tells us to keep a clear mind so we can avoid confusion. What is the actual goal? Clear and accurate perception of the truth. There is an allusion to reflecting reality without distortion. This means keeping our thoughts firmly in the present. It’s only by dwelling on past events or fantasizing about the future that we become distracted from what’s happening in the here and now. So to attain the “correct state of mind,” we need to cultivate a calm awareness of the present situation.

The second principle refers to a dignified appearance in which mind and body are one. This means having integrity. To integrate the mind and body, we must ensure that our actions match our intentions. If we say one thing and then do another, we “look” bad. This is just as true in kamae - mental preparation must support our physical preparation. Otherwise, our opponents will see through the illusion. Most adults can smell bullshit from a mile away, so our preparation and appearance must be genuine.

The third principle is difficult to express in English. We should make our ki spring up from the tanden, and this will keep us from “trembling” from fear. Ki has a bad reputation in the West because it is unfortunately associated with a lot of the mystical BS parlor tricks that people try to pass off as demonstration of martial arts mastery. But ki is really just a word for energy, and for our purposes, it can be summed up as the combination of proper breathing and mechanics. Breath control is the easiest way to affect our Central Nervous Systems, which impacts emotional arousal, power generation, and stamina. Proper mechanics assures that our movements will be efficient and effective. This is ki, and using it well is the goal of the gojokun’s third principle.

The fourth principle deals with training. It must be emphasized here that Shukumine viewed theory and practice as two sides of the same coin. In a Taido context, training includes study. The principle is that we must practice and study deeply. Having done so, we will know what to do at crucial moments. The more thoroughly we train our minds and bodies, the more easily we can make movements and decisions without having to stop and consider.

The last principle is my favorite. It tells us to adapt to our environments without going against the current of change. Taido’s techniques are designed so that defense transitions smoothly into offense. We use continuous movements so we can respond creatively to situations without the repeated necessity to stop and reset. Of course, there are limits to how we can move, for example, those imposed by gravity. So we should seek to remove unnecessary limitations and increase our freedom of motion (and thought) to allow ourselves the maximum possible expression of creativity in the moment.

That pretty much sums up my ideas on each point, but it doesn’t get us much closer to a handy cheat-sheet version. Now that I’ve explained each point at length, let’s strip them down to the bare essentials and create some rules we can use.

Rules We Can Use

When I started my dojo at Gerogia Tech, I had to think a lot about how to teach the various components of Taido. I felt that understanding the gojokun was an important part of learning Taido, but I couldn’t see my students getting much out of the version I had learned. I decided to work on a new interpretation.

What I had hoped to accomplish with this was something that my students could look at and say "Hey, that makes sense for combat as well as more peaceful aspects of my life." I tried to make sure that they could understand how each point could be applied to a variety of different venues (and even tested their ability to do so).

Tech Taido Version

This is how I broke it down a few years ago for my students at Tech:

- If our minds are clear and calm, we can perceive reality.

- If our minds and bodies are united in purpose, we can exceed our expected limits.

- If we employ proper breathing and mechanics, we can move well.

- If we practice well, we can be sure to act appropriately.

- If we are adaptable, we can always find a solution.

I was pretty happy with this version, even though I knew it wasn't expressing 100% of what's written in the original Japanese. However, basing my judgment of quality on the ability to create a positive outcome, I wasn't concerned with preserving any of the original "flavor." Instead, I opted for something that would improve my students' understanding of Taido and enrich their practice. But then I took that idea to an even greater extreme.

Taido's 5 Principles in Operational Language

In most of the interpretations above, each principle is stated as an if/then, as in the original Japanese version. I find this to be a rather abstract way of expressing prescriptions for action. If we are really trying to state the Five Simple Rules for Taido, can't we just lay them out like, well... rules?

Most [good] scientific literature is uses operational language in order to make sense and avoid inaccuracies. I feel it's helpful to state the ideas in the gojokun as directives, so we can better intuit their immediate applicability.

Here are the 5SRs in operational language:

- Keep you mind clear and in the present.

- Focus your intention with your actions.

- Breathe appropriately to generate power and control your emotions.

- Use your training to guide your judgement.

- Adapt to the situation and don’t fight changes.

This gives us a set of simple instructions that we can enact now, at this moment. Each point is simple and useful. We can see from these rules exactly what we must do to be more effective in anything. It isn’t poetic, and you won’t be able to impress people by talking like a wannabe samurai with this version, but that’s precisely why it works.

These points can be used during classes to focus a student’s attention on a specific idea without interrupting the flow of practice. I introduce them one at a time to beginners, usually without mentioning the gojokun at at all. Once I’ve done that, I can use them as cues anytime that student needs a quick reminder. If a student is setting stuck in jissen by trying to apply a certain technique, it’s often enough for me to simply say “adapt!” and the student will stop resisting the flow of the match. This isn’t always the case, and it’s not automatic, but it it possible when we use operational language for the gojokun.

Finding Taido’s Core Values

So what do all these interpretations have in common? Let's try boil each of these five ideas down into a value that the rule attempts to express.

The 5 Core Values

- Awareness and clear perception

- Integrity and preparation

- Correct breathing and movement

- Judgement based on study and training

- Adaptability, freedom, and creativity

These five points seem to sum up the desired end product of each version of the 5jokun above. Whereas the operational version gave us Five Simple Rules, the above list gives us 5 goals to shoot for in everything we do.

Use It

News Flash: Students can learn more easily if they know what they are supposed to be learning. Up to now, we've been making them memorize the rules and telling them that they have to understand the concepts the rules imply. I'm suggesting that we begin by telling them the concepts and asking them to experiment with applying them.

The 5SRs as a Teaching Tool

Perhaps it would be beneficial to our students if we taught them what we wanted them to know. I mean, what's the point of rote memorization and occasional chanting of vaguely-worded philosophies? It will serve everyone better if we can simply remind students at appropriate times of the values they are expected to cultivate by certain practices. This way, students can internalize the desired concepts readily.

Goal-directed learning is student-centered. By phrasing the 5jokun in terms of the 5SRs or as five values, we give students an idea of where they should be heading. This puts their practice into perspective and allows them more freedom in experimenting (thus bringing new, creative ideas to Taido) while still being certain that they are working within the framework of Taido's value system.

While there are still many factors in Taido's educational model that could use a lot of re-working, adopting a workable version of the 5jokun such as those provided above will be one step in the right direction towards a more effective method of teaching.